Meet the Guy Who Died While Playing Organ in Notre-Dame de Paris

Some added notes to today's podcast episode

Before we start, some book news: My most recent novel, Bastards of the Revolution, reached #14 on Amazon a few weeks ago. Plus, a book club has just picked it up. And Pigeon hit #1 in young adult mysteries. So I’ve been celebrating.

On to the topic at hand:

As you probably already know, I create the score for a popular podcast about Paris called The Earful Tower. This season, host Oliver Gee is running through the A-Z of Paris and France. Literally. Each new episode is themed by a letter. And I create a soundtrack tailored to each episode’s theme.

Today’s episode is N for Notre Dame. You can hear the episode here. And that’s what led me to an incredible anecdote about the musician who died while playing the organ in Paris’s most famous cathedral.

First, I fell for Notre-Dame de Paris when I was 16. Loved the vibe of the place. Loved the neighborhood. Loved the view from the top. Loved everything.

In more recent years, I love waking up early and walking through the cathedral when I’m in town. I’m not Catholic; I’m just there for the history and the quiet.

So needless to say, I was very happy to explore a musical choice for this week’s Earful theme.

As with all episodes, I research before I record any music. It turns out, there has been an organ in Notre-Dame since 1330. In the 1790s, revolutionaries stole pipes and melted them into bullets. Today, it’s the largest organ in France. 5 keyboards. 8,000 pipes.

Miraculously, the fire in 2019 didn’t damage the organ. However, restorers are taking this opportunity to clean it, which apparently was very badly needed.

Next, I started listening to live recordings of the Notre-Dame organ. And let me tell you, that’s a delightful and deep rabbit hole. And the first name I saw? Olivier Latry.

Monsieur Latry is the current organist at Notre-Dame, a professor of organ at the Conservatoire de Paris, and a notable composer and improvisor. In fact, here’s a video:

I’ll address improvisation here in a second, but I can say this: I didn’t know organ improv was a thing at all, let alone a big deal. Turns out, it’s both.

And one side note here before I continue: just look at that organ console. Thousands of tonal options. What a beast. Here’s the modest heat I’m packing in my little studio. It’s more impressive for the amount of nerdiness sitting on it than the organ itself.

So I read up a little about Olivier Latry, and that led to me to his predecessor, Pierre Cochereau. I found some wonderful recordings there as well. He was the organist at Notre-Dame from 1955-1984. After he died, the Conservatory of Nice was named after him.

So I thought, “Okay, here’s my guy.” But then I got distracted by this:

Just shy of his 13th birthday, on 2 June 1937, Cochereau laid hands on an organ keyboard for the first time. Coincidentally, that was the exact day that Louis Vierne, “the then-organist of Notre-Dame-de-Paris, died at the console of the organ.”

When I read that, I thought, “NOW THAT’S A STORY.” So here it is.

Louis Vierne was born in France 153 years ago this coming weekend. How apt. He was born mostly blind due to congenital cataracts (I won’t pretend I didn’t have to look that up to find out what it was), but it didn’t hamper his musical ability. He was picking out Schubert lullabies on the piano as early as age 2. Yikes.

At age 6, he underwent a surgical procedure to remove part of his iris. This helped his eyesight improve substantially. He could discern shapes and people and even large lettering. Side note: I shudder at the thought of what eye surgery in 1876 looked like.

Anyway, he learned braille and took piano lessons as a child. He started playing organ in 1881, and was admitted as a student at the Conservatoire de Paris in 1890. This was also the same year he became the organist at Saint-Sulpice. He was 20 years old. Good gig.

And then in 1900, at age 30, Louis was named the titular organist at Notre-Dame de Paris. He had a distinguished career as a composer and performer. He toured globally, and was awarded the Chevalier de la Legion d'honneur in 1931.

His health deteriorated in ‘35 and ‘36. That brings us to the evening of 2 June 1937.

Apparently, his mobility in his later years took a significant hit, and he’d even declared that it was time to start looking for his successor at Notre-Dame. Amazingly, the recital he gave on the day he died was his 1,750th in the cathedral.

Yes, you read that right. 1,750 concerts in the same venue. Unreal.

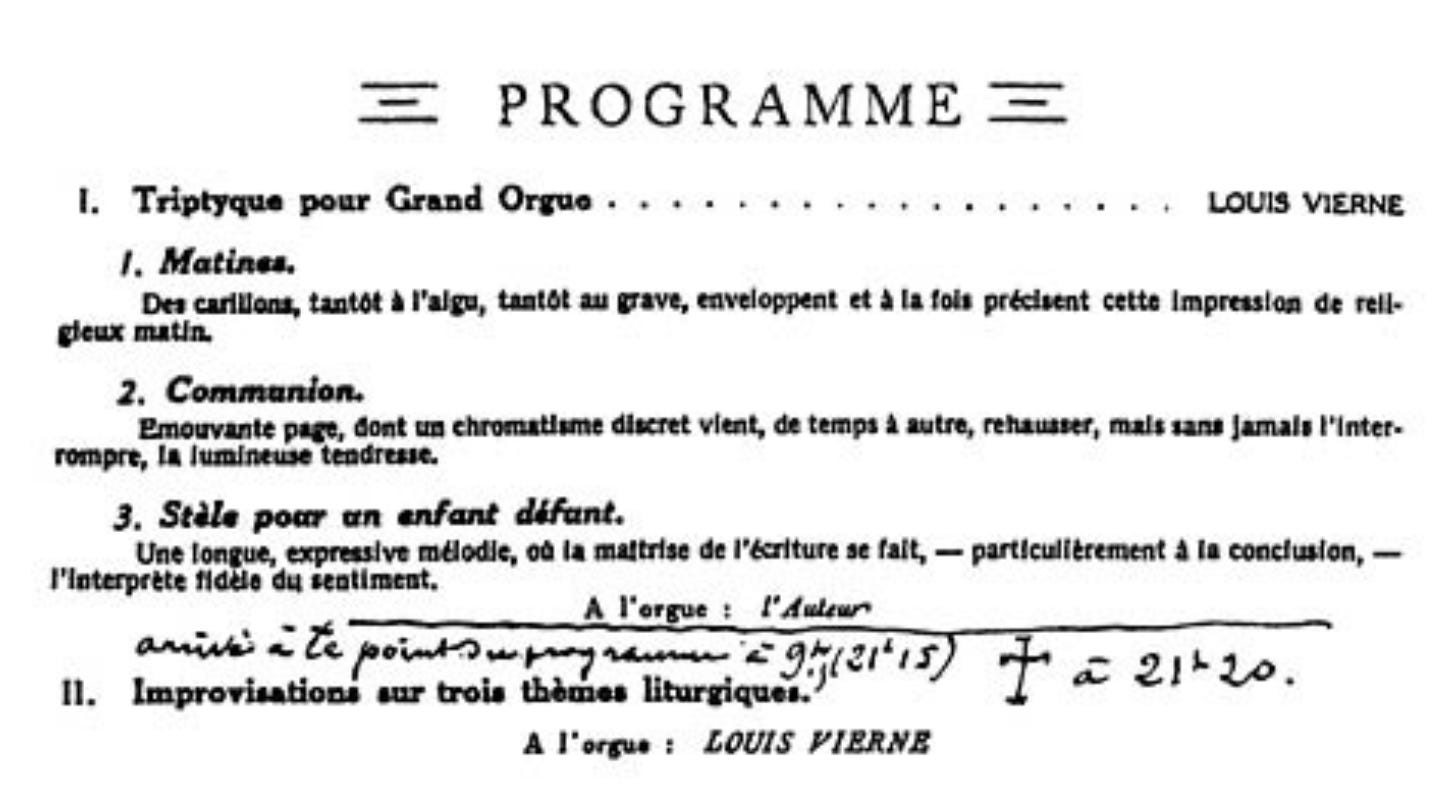

For that show, he performed all three movements of his composition, Triptyque, Opus 58. Here’s what that sounds like, played in a cathedral in Antwerp:

Despite looking gaunt and needing help getting to the console, audience members said that he played as well or better than he ever had. For the final part of the concert, he was going to improvise three pieces.

But it never happened. According to this article, “Vierne turned pale; his right hand trembled and clutched at the manual. ‘I can no longer see the keys’ he said, and ‘I am going to be ill’. Then, he collapsed at the organ with his foot pushing down the low E pedal for a while, causing a single tone that echoed through the cathedral. He was dead instantly. The audience was later informed about what happened... Prayers were said before Vierne’s corpse was moved downstairs to an ambulance car and taken to his apartment.”

Here’s the program from the evening.

After reading about all this, I knew that we’d use a portion of Triptyque on the Earful Tower this week. I listened to it, and all three movements are incredibly creative. But I like the second part, Communion. The melody felt like something I could use in my own way. And I like that it’s well-named to fit the theme of a cathedral.

First thing I did (and always do): record a drum track. After rehearsing the melody a little on the organ, I realized I’d need to bump the tempo up from 60 beats per minute to 80. So that’s what I did—first drums, then organ.

Then I played some piano chords beneath the melody. This is the heart of my departure from the original recording. They aren’t Vierne’s. I matched my own chords to his melody, which inspired me in ways that wouldn’t have happened had I been the sole composer.

While I’m always trying to stay true to the theme of the episode, I also stay true to my own style. And not least, I need to match Oliver’s level of energy as the podcast host. It’s okay for a slower, more somber tone to a podcast soundtrack if the subject matter warrants it, but I never want to put the audience to sleep.

Anyway, I added bass, an acoustic guitar solo, and then an organ solo before returning to the original theme. Et voilà, the track was done. Here it is:

I mentioned improvisation above. In brief, and for those unaware: when a musician makes up music as it’s being performed—that’s improvisation. I’m not an expert in the history of it, but when I think of improv, I think of jazz. Jam rock too.

Until now, I’ve never heard of entirely improvised organ compositions. I guess I never had a reason to dive into the world of organ improv. And I’m really glad I did. It has blown my mind.

I think improvisation is a huge part of being a musician. Particularly, in live performance. As an audience member, I love knowing that I’m seeing a moment that will never be replicated in the exact same way. This is personal. This is for us only.

But improv is tricky. From a performer’s perspective, I can say: it’s hard to improvise something and think it went perfectly. Maybe that’s part of the magic. Or maybe it’s really frustrating. Or maybe it’s both. And if you’ve made it reading this far, I’ll reward you with this video. It’s a good metaphor for how it feels when an improvised solo goes wrong.

Just glad that guy’s okay.

Anyway, on this song, both the guitar and the organ solos are improvised. There has been at least one improvised solo on almost every track I’ve ever done for Earful.

But I’ll be straight with you: the guitar solo on this track crashed on the first take like the fortunate soul above. So in the final recording, it is actually three improvised takes spliced together to make one solo. Ah, the luxuries of recorded music.

To me, that’s why live performances like Olivier Latry’s and Louis Vierne’s are so impressive.

So, there you have it. This entire story inspired me to play a little more organ than I usually do. So, keep your eye on my instagram and there will be some organ videos there this week. And I promise, as a nod to Monsieur Vierne, some improv.

Here’s my last note. I came across another mind-blowing fact: before the fire, anyone was allowed to play the organ at Notre-Dame de Paris. It existed for all to enjoy. However the sign-up list was 3 years long.

But I think my destiny is clear. If they start taking names again when the restoration is complete, I’m gonna work to get on that list.

Thank you, Pres. I learned so much by reading your post today, about Notre-Dame de Paris, about organs and organists, about improvisation and about how you compose your pieces for The Earful Tower. Lovely composition.

Very interesting Pres! Your instrument collection is impressive. and P.S. thanks for becoming my first ever subscriber :)